Arthur

Edward Clabburn (1849-1901)

and Rosey de Pearsall

(c.1861-1922)

Biographical Notes by John

Barnard

Updated 20 Apr 2020

My maternal grandmother was Ethel de Pearsall Clabburn (1879-1960), eldest of the six children of Arthur Edward Clabburn and Rosey de Pearsall.

Arthur Clabburn

was born in the hamlet of Thorpe, on the outskirts of Norwich, Norfolk,

on 7 April 1849, the second of the six children of William

Houghton Clabburn, a prosperous Norwich businessman and art

patron, and his wife Hannah

(née Blyth). When he was about 11 he, along with his

siblings, was a model for the Study

for Spring (right - Arthur is probably the boy shown on

the far right of the picture) by the artist Frederick Sandys, who was a

friend and beneficiary of his father's patronage.

Arthur Clabburn

was born in the hamlet of Thorpe, on the outskirts of Norwich, Norfolk,

on 7 April 1849, the second of the six children of William

Houghton Clabburn, a prosperous Norwich businessman and art

patron, and his wife Hannah

(née Blyth). When he was about 11 he, along with his

siblings, was a model for the Study

for Spring (right - Arthur is probably the boy shown on

the far right of the picture) by the artist Frederick Sandys, who was a

friend and beneficiary of his father's patronage.

Initially Arthur took up a military career and aged 19, on 16

Oct 1868, he was commissioned as an Ensign in the

75th (Stirlingshire) Regiment of Foot. (Under an army

restructuring in 1881, the 75th Regiment became the 1st Battalion of

the

Gordon Highlanders and some sources refer to Arthur having

served in this regiment.) He also developed a friendship with Sandys,

and many years later his daughter Ethel recalled, in a letter to the

Times [CLA/19],

her father's stories of being taken by Sandys as a

young subaltern to meet Dante Gabriel Rossetti and other member of the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood at Rossetti's house in Cheyne-Walk, Chelsea.

Around the time he was commissioned, and possibly at the wedding early the following year of his younger sister Mary to the heir to the Crosse & Blackwell tinned food firm, Arthur met and fell in love with a 17-year-old girl called Emilie Isabella Roumieu. She was the daughter of the well-known architect R.L. Roumieu (1814-1877), who had designed a number of warehouse buildings for Crosse & Blackwell. Their relationship seems to have developed swiftly, but by May of 1869 Arthur had been abruptly posted to Hong Kong, and a long separation was in prospect. He wrote to her explaining his position, but she agreed to wait for him, and in a very correct Victorian manner, he also wrote to her father asking for his consent to their continuing relationship - a letter which survives [CLA/16/1]. Father evidently did consent, and Emilie also became a great favourite of Arthur's parents.

So things continued for the next two and half years, during which Arthur was promoted to Lieutenant, but in November 1871, while on home leave at his parents' house in Norwich, he wrote again to Emilie's father [CLA/16/2], recognising that so long as he remained in the army he would not be in a position to support a wife, though adding "I live in hope of something coming in my way which may enable me to give up the army, and thus attain my wishes". If this was a hint to Roumieu that a substantial dowry, or the offer of employment in his architecture practice, might be the "something coming in his way", it was not taken up, and Roumieu's reply [CLA/16/3] acknowledged Arthur's sacrifice of his feelings in recognising the situation, but expresed his own opposition to a long prospective engagement.

Emilie was thus released from her commitment to Arthur, and in 1875 she married one Alexander Coghill Wylie (c. 1852-1908). She may well have regretted her decision not to wait for Arthur, as after just eight years of marriage she sued Wylie for divorce on grounds of both adultery and violence, obtaining custody of their two children. Wylie fled to Australia to escape his creditors, where he remarried and fathered the lesbian feminist author I.A.R. Wylie, whose autobiography is not complimentary to him.

Manwhile Arthur travelled extensively with the regiment, also serving in Singapore, Mauritius and Natal. However, on 3 Jul 1872 he was placed on the "half pay" (i.e. reserve) list and he retired from the service on 24 Mar 1875 (just short of his 25th birthday), when he "received the value of his commission". This may have helped him set himself up as a freelance artist, initially living with his parents in Norwich, and he had pictures shown at the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition in 1875 (No. 1064 "Miss Fanny Jecks"), 1876 (No. 1142 "A Portrait") and 1879 (No. 1397 "Portrait of a Lady"), though if these pictures survive, their whereabouts are unknown.

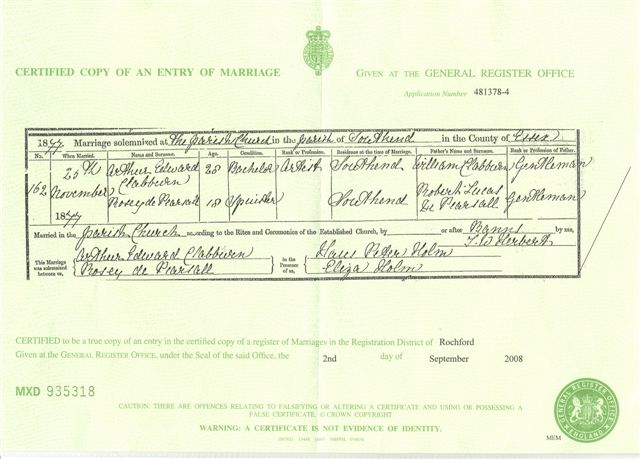

In 1877, Arthur married Rosey

de Pearsall, the wedding taking place in the parish church

of St John the Baptist in Southend-on-Sea on 25

November, after Banns had been published on 30 September, 7

and 14 October. Both bride and groom are

stated on the marriage certificate [CLA/13/3] to

be resident in

Southend and the witnesses were a local painter-cum-plumber and his

wife,

Hans Peter and Eliza Holm. There is a family tradition among their

descendants that the wedding was not approved of by Arthur's parents,

and the choice of an out-of-the-way venue, and the absence of family

witnesses, suggest that it was undertaken clandestinely.

In 1877, Arthur married Rosey

de Pearsall, the wedding taking place in the parish church

of St John the Baptist in Southend-on-Sea on 25

November, after Banns had been published on 30 September, 7

and 14 October. Both bride and groom are

stated on the marriage certificate [CLA/13/3] to

be resident in

Southend and the witnesses were a local painter-cum-plumber and his

wife,

Hans Peter and Eliza Holm. There is a family tradition among their

descendants that the wedding was not approved of by Arthur's parents,

and the choice of an out-of-the-way venue, and the absence of family

witnesses, suggest that it was undertaken clandestinely.

Rosey

was the daughter of Robert

Lucas de Pearsall (the Younger) (son of the composer Robert Lucas

Pearsall) and Anna Maria Hamilton-ffinney (a grand-daughter

of Rev.

Samuel Lee (1783-1852), Professor of Hebrew

and Arabic at Cambridge University). However, I

have been unable to trace a birth record for her, and it seems likely

that she was

born out of wedlock, around 1861, with

her parents not marrying until 23 Mar 1864. Census returns give

inconsistent

ages for her (though that of 1881 records that she was born in the

Paddington district of London) and her death certificate in 1922 gives

her age as 60. The marriage certificate gives her age

as 18

(implying a birth in 1859), but this is almost certainly

false, and aimed at avoiding the need for parental consent to the

marriage; family

tradition is that she was 17 when her eldest daughter Ethel was born in

April 1879.

Despite coming from "good" families, her parents seem to have been somewhat impoverished. Her father had been previously married; he is shown as living in Chelsea with his first wife in the 1861 census, though I have been unable to discover what happened to her. He died in mysterious circumstances (found drowned in a canal in the East End of London, close to where the Olympic Stadium now stands) in December 1865. Extraordinarily, Rosey's mother remarried less than three weeks later, though her new husband, Charles Graham Carttar (1835-1917) later emigrated to America with another wife [CART/2]. He is shown as married but living on his own in London in the 1871 census, and I cannot find Rosey's mother in that census, though it is possible that she was abroad with her widowed father-in-law, who is similarly absent. Rosey's mother died of breast cancer in 1880, two and half years after Rosey's marriage, but her death certificate incorrectly records her as Carttar's widow, and the death was reported by her brother Samual Lee Hamilton-ffinney.

What contact Rosey retained with her mother, her stepfather, or her father's family remains very unclear. Presumably some financial provision was made for her, though I do not know who by. She is recorded at a small private boarding school near Liverpool in the 1871 census (when she would have been about ten), run by a Mrs Annie Binks, of whom she is supposed to have been very fond [CART/2]. I also have some elegant visiting cards, in the name of "Miss de Pearsall", suggesting that even in her mid teens she held a certain status in society.

Rosey was certainly in touch with Philippa Hughes, her father's younger sister, and I have a brief note from Philippa to Rosey [CLA/15], dated less than two weeks after her wedding to Arthur, which implies that Rosey had returned to London from Southend, but it makes no mention of the marriage. Her father's elder sister, Elizabeth Stanhope, had become the Countess of Harrington when her husband had rather unexpectedly inherited the Earldom on the death of a young cousin in 1866, and he was now one of the richest landowners in the country. Either sister could certainly have provided financial support for Rosie.

Whatever contact she might have had with her stepfather Graham Carttar, Rosey did remain in touch with his family, which included several maiden sisters, one of whom wrote to Arthur shortly after the birth of Arthur and Rosie's first baby in 1879 [CART/1]. Rosey's step-grandfather Charles Joseph Carttar (1809-1880) was the Kent Coronor, a position later occupied by his younger son, and they might also have provided some financial help. Though Charles Joseph died in 1880, he left no will (somewhat negligent for a coroner!), so there is no opportunity to see if he might have left a legacy to Rosie [CART/4].

Whatever the circumstances surrounding its start, Arthur's and Rosey's marriage seems to have been a happy one. Ethel, the first of six children, was born in April 1879 in Kensington, and their address is given as 159 High Street, Notting Hill in the catalogue for that years Royal Academy summer exhibition.

By the time of the 1881 census they had moved to Underdown Road, Herne, near Canterbury in Kent, and their next two children were born in Kent. For the 1891 census they were back in London, at St Marks Road in Kensington, though I have not been able to find a record for them in the 1901 census. Whatever strains there may have been in Arthur's relations with his father (his mother died a few months after his marriage), they appear to have been at least partly patched up, and there is no truth in the family legend that he was disinherited. As revealed in his father's will [CLA/10], dated 1888, he took out a life assurance policy with the Norwich Union on Arthur's life, presumably in order to ensure that some provision would be made for the children in the event of Arthur's demise (I am hoping to discover some details of this from the Group Archivist at Aviva plc, the present-day incarnation of Norwich Union). The benefits of this policy were bequeathed to Arthur on his father's death the following year, along with a cash sum of £400 (equivalent to about £37,000 in today's terms). This inheritance was no doubt a considerable help to Arthur and Rosey's probably rather "hand-to-mouth" finances, which were otherwise dependent on whether or not Arthur had been paid for any art commissions. In the family's oral tradition there are (possibly apocryphal, and no doubt embroidered) stories of midnight flits from one house to another, when the rent could not be paid, and great generosity to friends and neighbours when money was suddenly plentiful. A family saying that has been perpetuated though the descendants of more than one of their children is "it's only money".

Arthur does seem to have been able to obtain a number of commissions from quite well-to-do clients, as discussed below, but in the early summer of 1901 disaster struck and he was diagnosed with stomach cancer - the disruption assocated with his initial illness might account for the family's omission from the 1901 census. Arthur died at 108 Sarsfeld Road in Balham, South London on 17 November 1901, aged only 52. Rosey was left with no income and with six children, ranging from Ethel, the eldest (22), though Charles (20), Adèle (16), Walter (12), and Dorothy (9) down to Viva (6). Family tradition is that Rosey had something of a drink problem, and was unable to cope with the responsibilities of single motherhood. It therefore fell to Ethel to take on the burden of ensuring that the family was provided for - this was before the days of the welfare state!

Ethel herself took a residential job as matron at Monmouth School, while Rosey was eventually settled in a boarding house in Brighton, where she is recorded in the 1911 census. There were already some family associations with Brighton, as the 1901 census (taken on 31 March) shows Adèle at boarding school there, and Ethel herself may also have had some education at the same place [LJ/3].

In 1906 Arthur's nephew Edmund Mitchell Crosse, now the heir to the Crosse & Blackwell food firm, married Leda Roumieu, a niece of Arthur's early love, Emilie, thus finally providing an indirect marital link between the Clabburn and Roumieu families. This might have been the occasion for the re-establishment of contact between the divorced Emilie and Arthur's family - certainly there must have been contact at some point, as Arthur's letters to Emilie's father, mentioned above, somehow came into Ethel's possession. My mother (Ethel's daughter) told a story of how Ethel managed to obtain some financial assistance from the Crosse family, and perhaps Emilie had a part to play in this. Two of Arthur's aunts (Amelia Dunnett and Elizabeth Pearce) had married rich husbands and were living in London at this time, and might also have helped.

Rosey lived on at Brighton until 17 January 1922, when she died of acute bronchitis, complicated by heart failure, aged about 60. My uncle, Bob James, told me that he remembered being taken to visit her, his grandmother, aged about 4 (which would put the visit about 1920) and climbing the stairs to her room in the boarding house at 36 Norfolk Road. He recalled a distinctive smell, which he was quite certain was gin - the classic "mother's ruin". Rosey had a chequered life, born in straightened circumstances, almost certainly out of wedlock, with a father who had once owned a castle in Switzerland, but was drowned when she was only about three years old, and a stepfather who seems to have abandoned her mother; she was brought up at a boarding school in the north west and married at 16, yet she was first cousin to one of the richest noblemen in England. Nevertheless, she seems to have had 23 years of happy-go-lucky marriage to a struggling artist, raising a brood of children, whose descendants are still in regular contact with each other more than a century later, and it perhaps isn't too surprising that she took to the bottle after his tragically early death.

Arthur's Pictures

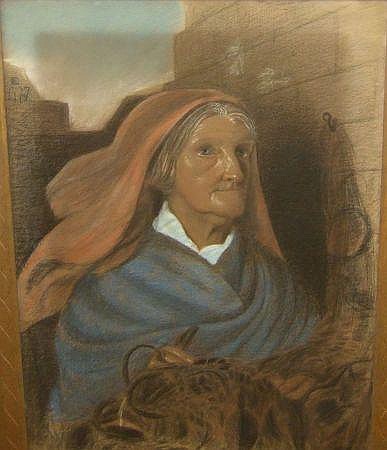

The

fate of the three early pictures

shown at Royal Academy summer exhibitions, mentioned above, remains

unknown, though

another picture from this period, an

1877 Portrait

of a Fisherwoman (right) was sold

for £10 by a Norwich auctioneers in 2012.

The

fate of the three early pictures

shown at Royal Academy summer exhibitions, mentioned above, remains

unknown, though

another picture from this period, an

1877 Portrait

of a Fisherwoman (right) was sold

for £10 by a Norwich auctioneers in 2012.

Arthur's success in getting commissions after his marriage was

probably quite patchy, and I those of

his surviving pictures which I have managed to trace has largely been

the result of the owners finding this website when searching his name.

In 2015 I was

contacted by an antique dealer, who had come into posession of a signed

oil-on-canvas portrait showing a Roman Catholic

cantor priest; this was subsequently purchased by my cousins Linda

(née

Adamson) and Nicholas Payne, who had it restored in 2018 (left). As

yet we have not been able to identify the sitter.

In 2019 I was contacted by the owners of a "portrait of a lady" (right), signed and dated 1888. The origins and provenance of this picture are unclear as the owners acquired it in the 1980s with the house in Ireland where it still hangs.

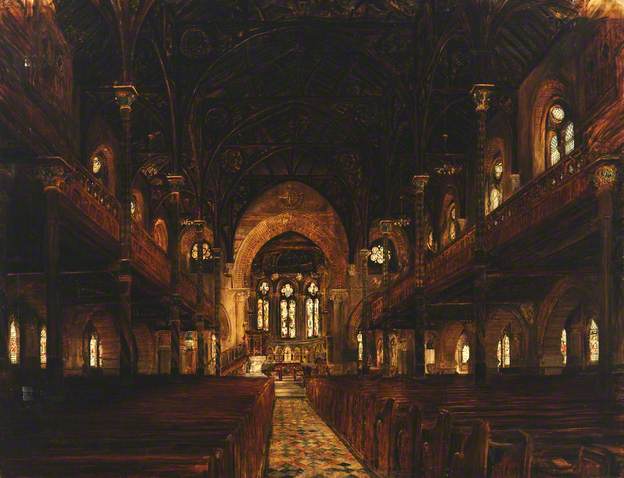

In 1891 Arthur sold a

picture of the interior of St Mary's Church at Ealing

(left) to Ealing Central Library in west London, where it remains to

this

day.

In 1891 Arthur sold a

picture of the interior of St Mary's Church at Ealing

(left) to Ealing Central Library in west London, where it remains to

this

day.

I also hold a photograph (right) of a portrait, identified on

the

reverse

as being of "Bertha Tufnell wife of Colonel Tufnell" and

noted on

the front, in the hand of Arthur's daughter Ethel, as being "from an

oil painting life size by A. E. Clabburn". Ellen

Bertha

Tufnell, née Gubbins (1867-1930) was the wife of Lt.-Col.

Edward

Tufnell

(1848-1909), MP for Essex South East 1900-1906, and the family gave its

name to the North London suburb of Tufnell Park. My attempts to

identify and contact descendants of the sitter, to see if they still

have the picture, have not so far been successful.

Arthur's

descendants possess three of his portraits of family members. The one

of his

wife Rosey, shown above, is held by my cousin Rosetta Plummer,

née

James. A crayon drawing

of his sister Lucy Clabburn (left) is held by my sister Anne Barnard

and an

oil-on-canvas

portrait of his eldest two daughters (right), painted shortly before

his death hangs above the fireplace at my own home - a

high-resolution version can be downloaded by

clicking on the image.

Children and Descendants

Ethel de Pearsall Clabburn (12 Apr 1879 - 29 Feb 1960) took a job as Matron at Monmouth Grammar School, which no doubt brought in some much needed income. After a new Headmaster, Lionel ("Leo") James (1868-1948) took up his position in 1906, a slow-burning romance led to their marriage in 1912 and five children, including my mother.

![Charles Clabburn [CLA/32/1] Charles Clabburn [CLA/32/1]](CLA-32-1%20Charles%20ES%20Clabburn.jpg) Charles

Edward

Stuart Clabburn (23 Jun 1881 - 6 Aug 1965) emigrated to

New Zealand, where he became a successful

businessman, initially importing the type of silk shawl his grandfather

had made.

He married Clara Hitchcock (9 Jul 1882 - 10 Feb 1966) and

they adopted a daughter, Penelope.

Charles

Edward

Stuart Clabburn (23 Jun 1881 - 6 Aug 1965) emigrated to

New Zealand, where he became a successful

businessman, initially importing the type of silk shawl his grandfather

had made.

He married Clara Hitchcock (9 Jul 1882 - 10 Feb 1966) and

they adopted a daughter, Penelope.

Adèle Vandeleur Clabburn (27 Dec 1884 - 7 Jun 1923) married a Scottish landowner, James Bertram Roberton (3 Nov 1879 - early 1940s) in London on 19 Jan 1907. James Roberton took his wife to Australia where he worked a farm property near Dalby in Queensland, later selling his estate in Scotland to an uncle. Walter Lionel Clabburn (10 Jan 1889 - 16 Aug 1951) went to join them in Australia in 1910, but the property failed following a prolonged drought, and Walter and the Robertons went their separate ways. Adèle died of cancer in 1923, leaving a son and two daughters, while James Roberton himself seems to have disappeared. Walter moved to Sydney and married Marjorie ("Madge") Camplin Sommerville (22 Aug 1890 - 4 Jul 1977) on 23 Dec 1914 and had five children.

![Dorothy Clabburn, circa 1908 [CLA/32/2] Dorothy Clabburn, circa 1908 [CLA/32/2]](CLA-32-2%20Dorothy%20Clabburn%20c1908.jpg) Dorothy de

Pearsall Clabburn

(30 Jan 1892 - 23 Apr 1970)

married Cyril Hearne ("Billy") Pearson (14 Jul 1886 - 7 Feb 1946), an

assistant master at

Monmouth School, where her brother-in-law was the Headmaster. It is

interesting to note that, though Dorothy and Billy attended the wedding

of Ethel and Leo in 1912 as a couple, they did not marry themselves

until

four years later, on 8 Apr 1916; this possibly reflects the relative

earnings of the two schoolmasters. They had three children,

including the well-known character actor Richard Pearson (1918-2011).

Dorothy de

Pearsall Clabburn

(30 Jan 1892 - 23 Apr 1970)

married Cyril Hearne ("Billy") Pearson (14 Jul 1886 - 7 Feb 1946), an

assistant master at

Monmouth School, where her brother-in-law was the Headmaster. It is

interesting to note that, though Dorothy and Billy attended the wedding

of Ethel and Leo in 1912 as a couple, they did not marry themselves

until

four years later, on 8 Apr 1916; this possibly reflects the relative

earnings of the two schoolmasters. They had three children,

including the well-known character actor Richard Pearson (1918-2011).

![Viva Clabburn, circa 1908 [CLA/32/2] Viva Clabburn, circa 1908 [CLA/32/2]](CLA-32-2%20Viva%20Clabburn%20c1908.jpg)

![Viva Clabburn with Pascha and Trev James, 1927 [JAM/8] Viva Clabburn with Pascha and Trev James, 1927 [JAM/8]](JAM-8%20Viva%20Clabburn%20with%20Pascha%20and%20Trev%20James%201927.jpg) Viva

Winifred Clabburn (10 Jan 1896 – 14 Oct 1933) was

only five years

old when her father died, and ten years later the 1911 census (held on

2 April)

shows her as resident at the London Orphan Asylum at

Watford,

presumably because her mother was not in a position to look after her

as a child. However, at the end of that year she sailed for New

Zealand to join her eldest brother Charles in Wellington.

According to my mother, Charles's wife Clare found it difficult to cope

with Viva’s

vivaciousness, and she returned home in 1913. I am uncertain what she

did

during the First World War, but in 1920 she emigrated to the United

States; the record of her passage on the SS Adriatic

shows her

occupation as “domestic”. She returned to England

to visit her

family in 1927, and I have a photograph of her (right) with her sister

Ethel's

children on holiday at Bigbury-on-Sea in Devon. On 2 February 1929 she

married Charles

Edward Lawrence (c. 1895-1953) in

New York.

They settled in Chicago, and a daughter Patricia De

Pearsall Lawrence

was born there on 9 Oct 1933. Tragically Viva died just five days

later, presumably from complications of the birth, and Patricia (also

known as Patsy) was brought up by her

father, who regularly sent photographs of her to her family in

England [CLA/31].

Viva is buried with her husband at the Hillside

Cemetery in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

Viva

Winifred Clabburn (10 Jan 1896 – 14 Oct 1933) was

only five years

old when her father died, and ten years later the 1911 census (held on

2 April)

shows her as resident at the London Orphan Asylum at

Watford,

presumably because her mother was not in a position to look after her

as a child. However, at the end of that year she sailed for New

Zealand to join her eldest brother Charles in Wellington.

According to my mother, Charles's wife Clare found it difficult to cope

with Viva’s

vivaciousness, and she returned home in 1913. I am uncertain what she

did

during the First World War, but in 1920 she emigrated to the United

States; the record of her passage on the SS Adriatic

shows her

occupation as “domestic”. She returned to England

to visit her

family in 1927, and I have a photograph of her (right) with her sister

Ethel's

children on holiday at Bigbury-on-Sea in Devon. On 2 February 1929 she

married Charles

Edward Lawrence (c. 1895-1953) in

New York.

They settled in Chicago, and a daughter Patricia De

Pearsall Lawrence

was born there on 9 Oct 1933. Tragically Viva died just five days

later, presumably from complications of the birth, and Patricia (also

known as Patsy) was brought up by her

father, who regularly sent photographs of her to her family in

England [CLA/31].

Viva is buried with her husband at the Hillside

Cemetery in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

![Patricia Lawrence, 1953 [CLA/31/6] Patricia Lawrence, 1953 [CLA/31/6]](CLA-31-6%20Patricia%20Lawrence%201953.jpg)

![Patricia Lawrence wedding [CLA/31/9] Patricia Lawrence wedding [CLA/31/9]](CLA-31-9%20PatriciaLawrenceDirkDietrichSmithWedding.jpg) Patricia

visited

England in 1955, when she stayed with my parents in London, and she

and my mother corresponded at least until the mid 1960s. I understood

from my mother that she married “Dirk” Dietrich

Smith, probably

in the late 1950s (I have a photograph (right) of the bride and groom),

and they moved to Hawaii where they raised two sons,

“Chuck” and Todd. I have been unable to find a

record for the

marriage, but the Honolulu Advertiser for 13 Apr

2007

announced the death on 6 April of Dietrich

“Dirk” Smith IV

aged 72, and mentions sons Dietrich and Todd. I am endeavouring to

re-establish contact with this branch of Arthur and Rosey

Clabburn’s

descendants.

Patricia

visited

England in 1955, when she stayed with my parents in London, and she

and my mother corresponded at least until the mid 1960s. I understood

from my mother that she married “Dirk” Dietrich

Smith, probably

in the late 1950s (I have a photograph (right) of the bride and groom),

and they moved to Hawaii where they raised two sons,

“Chuck” and Todd. I have been unable to find a

record for the

marriage, but the Honolulu Advertiser for 13 Apr

2007

announced the death on 6 April of Dietrich

“Dirk” Smith IV

aged 72, and mentions sons Dietrich and Todd. I am endeavouring to

re-establish contact with this branch of Arthur and Rosey

Clabburn’s

descendants.

Family Trees of their Descendants

Arthur and Rosey now have over 200 descendants, who are scattered over four different continents, and need four separate family tree sheets to show them. I am in contact with all but Viva's branch of the family, and am endeavouring to keep the family trees listed below up to date. They have been compiled from information supplied to me by my cousins shown on them and I am always pleased to receive updates and corrections! (see contact details) Most of the people

shown are

still living, and for reasons of personal privacy and to avoid the

danger of identity theft, access to them is restricted to

family

members. A username and password are required

to see them, and can be obtained by sending an e-mail to me (see contact details). Further information is given on

the Family

Trees

index page.

Most of the people

shown are

still living, and for reasons of personal privacy and to avoid the

danger of identity theft, access to them is restricted to

family

members. A username and password are required

to see them, and can be obtained by sending an e-mail to me (see contact details). Further information is given on

the Family

Trees

index page.

- Ethel de Pearsall James (mainly UK) [Printable PDF]

- Charles Clabburn (New Zealand) and Adèle Roberton (mainly Australia) [Printable PDF]

- Walter Clabburn (mainly Australia) [Printable PDF]

- Dorothy Pearson (mainly UK) and Viva Lawrence (USA) [Printable PDF]