Henry James Catling Clabburn (James Blyth)

Notes by

John Barnard

Updated 7 March 2023

| Clabburn Family Tree (18th-20th centuries) |

| Catalogue of Clabburn source material |

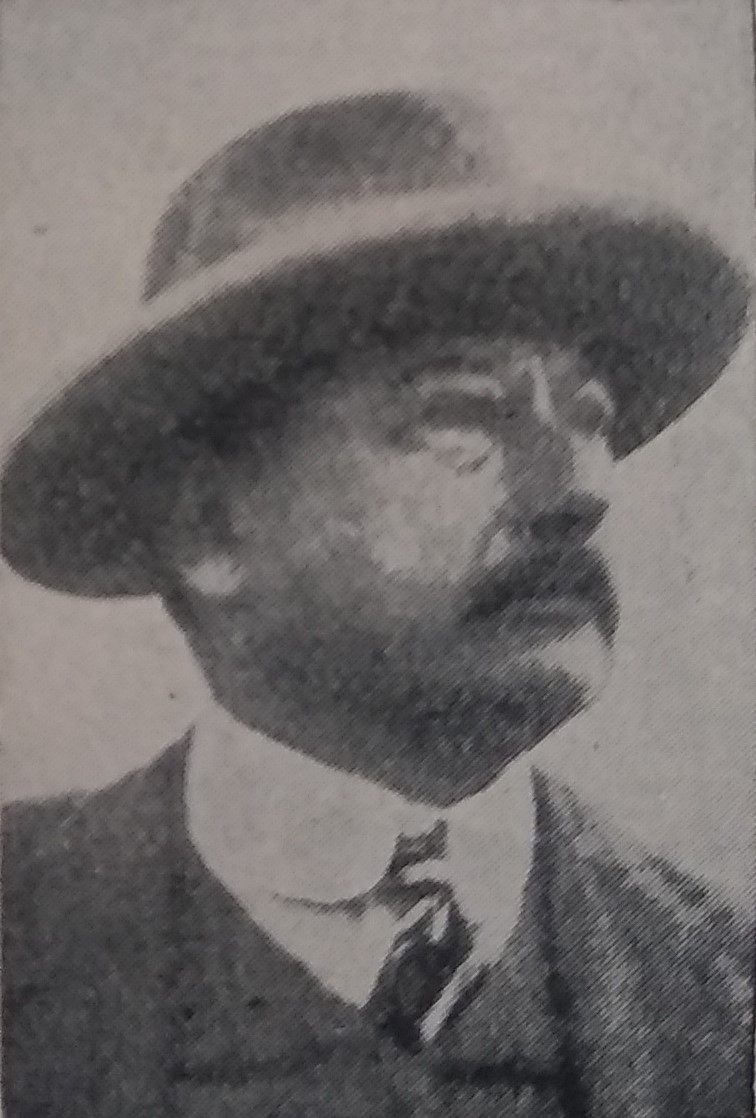

Henry James Catling Clabburn (1864-1933) was my great-grandfather Arthur Edward Clabburn's younger brother. He was born in Norwich, and after an initial career as a solicitor in London, in the mid 1890s he changed his name to James Blyth, moved back to his native East Anglia, where he spent the next twenty years or so writing nearly sixty published novels. Later in life he moved back to London, and taught for a while at the newly-formed London School of Journalism. His novels have attracted rather minor literary interest over the years, but my recent research has shown him to be one of the most interesting, if not the most sympathetic, of my Clabburn forbears.

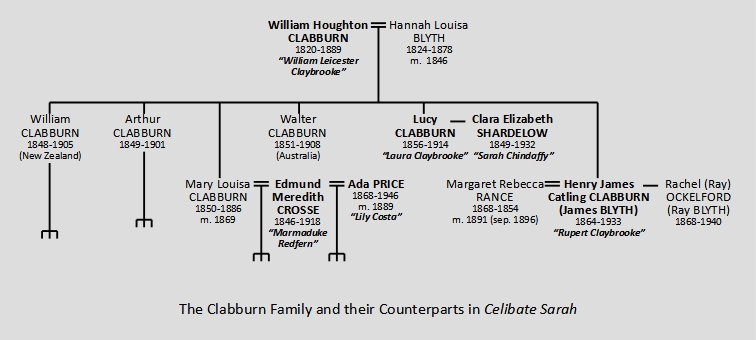

There is documentary evidence supporting a good deal of Henry's life history, but the background (if not the main plot itself) in the the second of his novels, Celibate Sarah, clearly has an autobiographical basis and features thinly-disguised versions of several members of Henry's extended family (there is a table of the correspondences below). Many of the known facts of Henry's life are reproduced so exactly in the novel that it is tempting to assume that other episodes in the life of the principal character (Rupert Claybrooke) are also based on Henry's own. In the following notes I have tried to indicate which statements are supported independently, and which based solely on the novel.

- Family and Early Life

- Death of Father

- Marriage, Separation, and the End of a Legal Career

- An East Anglian Thomas Hardy?

- Celibate Sarah — Merging Fact with Libellous Fiction

- Return to London, Teaching, and Death

Family and Early Life

Henry was born on 17 Jan 1864 in Norwich [CLA/58/6] and baptised at St Augustine's church on 29 March [CLA/58/5]. His father was a successful and wealthy Norwich businessman, William Houghton Clabburn (1820-1889), and Henry was by a considerable margin the youngest of his parents' six children (nearly eight years separated him from Lucy, the next youngest). The composition and history of the Clabburn family is exactly reflected by the Claybrooke family in Celibate Sarah, where the principal character Rupert Claybrooke's three elder brothers (representing William, Arthur and Walter) are dismissed in a single sentence as "scattered about the world - failures" (p.2). W.H. Clabburn's career as a rich and successful manufacturer of silk and woollen stuffs is matched by Rupert Claybrooke's father in the novel, where it is stated that "in his best days he had made eight or ten thousand a year, and spent the whole of it" (p.2), associating with and commissioning pictures from the brilliant Pre-Raphaelite band of artists (p. 9). W.H. Clabburn's particular friend and protégé, Frederick Sandys, made a drawing of Henry when he was aged about seven (CLA-29, no. 3.32 - now in Norwich Castle museum). Another parallel is the death of Henry's mother Hannah (née Blyth) in 1878, when Henry was just 14, after which he boarded at Norwich Grammar School, where he distinguished himself academically, musically and as a sportsman, both as an oarsman and at Rugby. One can imagine that this bereavement, and Henry's subsequent separation from his family, affected him profoundly, and this too is reflected in the novel where there are hints (pp. 4 and 281) that Hannah's death (aged 54) might have been hastened by the novel's chief villain (representing his sister Lucy's lifelong companion Clara Shardelow).

In 1882 Henry went up to Corpus Christi College at Cambridge, making him the only member of his family to receive a university education. He graduated B.A. and LL.B. in 1886, with 3rd Class Honours in the Law Tripos; he also rowed as stroke for the Corpus Christi VIII [CLA/3/6/6]. He moved up to London, and trained as a solicitor at Lincoln's Inn, and is recorded as such in the 1891 census, when he was lodging in Hampstead [CLA/59/1]. All this again parallels Rupert Claybrooke's career as related in Celibate Sarah. At the same time, Henry was having a few articles published, including one in the Pall Mall Gazette about his father's correspondence with the artist and poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti [CLA/37].

Though there is no other evidence to support the idea, in the

novel, at this stage in his

life, Henry's alter ego

Rupert Claybrooke is taken under the wing of

his wealthy brother-in-law Marmaduke Redfern. Marmaduke is

very clearly based on Edmund

Meredith Crosse

(1846-1918), widower of Henry Clabburn's sister Mary Louisa Clabburn

(1850-1886), and successor to his father Edmund Crosse

(1804-1862) as a

senior partner in the well-known food manufacturers Crosse & Blackwell.

The novel relates that they had been on close terms before the death of

Rupert's sister, and it would perhaps have been natural for Edmund to

have offered support and encouragement to the young graduate, newly

arrived in the great metropolis, especially following the death of

Henry's real-life sister, Edmund's wife Mary, the same year. The novel

also relates (p. 2) that by this stage William Claybooke's

fortunes had been considerably reduced as the Norwich weaving business

declined in the face of foreign competition - an undoubted fact related

by historians of that trade [CLA/41, CLA/27]

- and Henry's expectations

of a large inheritance might well have gone with them. As a designated

Executor, Henry might also have been aware that his father's will, made

in 1888, left the bulk of his remaining fortune in trust for the

benefit of Henry's surviving (and unmarried) sister Lucy. Edmund's

financial support would therefore have been very welcome, and the novel

relates (p. 47) how Marmaduke encouraged Rupert in expensive habits

with promises that "I'll see you right when the time comes", and

"it had been understood that Marmaduke was to buy him a partnership

[in a firm of solicitors] when he was sufficiently experienced" (p. 28).

Though there is no other evidence to support the idea, in the

novel, at this stage in his

life, Henry's alter ego

Rupert Claybrooke is taken under the wing of

his wealthy brother-in-law Marmaduke Redfern. Marmaduke is

very clearly based on Edmund

Meredith Crosse

(1846-1918), widower of Henry Clabburn's sister Mary Louisa Clabburn

(1850-1886), and successor to his father Edmund Crosse

(1804-1862) as a

senior partner in the well-known food manufacturers Crosse & Blackwell.

The novel relates that they had been on close terms before the death of

Rupert's sister, and it would perhaps have been natural for Edmund to

have offered support and encouragement to the young graduate, newly

arrived in the great metropolis, especially following the death of

Henry's real-life sister, Edmund's wife Mary, the same year. The novel

also relates (p. 2) that by this stage William Claybooke's

fortunes had been considerably reduced as the Norwich weaving business

declined in the face of foreign competition - an undoubted fact related

by historians of that trade [CLA/41, CLA/27]

- and Henry's expectations

of a large inheritance might well have gone with them. As a designated

Executor, Henry might also have been aware that his father's will, made

in 1888, left the bulk of his remaining fortune in trust for the

benefit of Henry's surviving (and unmarried) sister Lucy. Edmund's

financial support would therefore have been very welcome, and the novel

relates (p. 47) how Marmaduke encouraged Rupert in expensive habits

with promises that "I'll see you right when the time comes", and

"it had been understood that Marmaduke was to buy him a partnership

[in a firm of solicitors] when he was sufficiently experienced" (p. 28).

Death of Father

Henry's real-life father William Houghton Clabburn died in 1889, and the novel opens with an account of his fictional counterpart William Claybrooke's death, and Rupert's summons from London to be at his bedside. The late Margaret Langley, who lived in the old Clabburn family home of Walpole House in the 1990s, noted that the relevant passage appeared to be a description of the death of the author's father, and identified features of the house mentioned in it, as well as the real-life equivalents of others present [CLA/3/6/4]. The novel relates that William had suffered a series of strokes in his final months, which had rendered him speechless, and in the absence of other evidence, this seems quite likely - certainly an obituary for the real-life William [CLA/35] relates that illness had prevented from attending board meetings of the Norwich Union Insurance Society.

The novel goes on to describe the funeral, during which Rupert's brother-in-law Marmaduke boasts to him in crude terms of his plans to remarry: "Lily Costa - Katie's sister, you know, a schoolfellow of the girls'...She ain't pretty, and she ain't much better than a fool. But she took my fancy. I made up to her people. Of course they were only glad to be taken up by me. ... They live up the river at Teddington." Marmduke relates that Lily had initially refused him, but was persuaded by her father ("he hasn't got too much money you know") adding, "I'm going to settle £40,000 upon her". Again, the basic facts involved correspond very closely with the known facts about Edmund Meredith Crosse's second marriage. Henry's sister Mary had died in 1886, leaving Edmund with five children aged between 2 and 15 (a sixth child had died in infancy). On 26 Oct 1889, just three months after W.H. Clabburn's death, Edmund married Ada Caroline Price (1868-1946). Ada was aged just 21 (compared to Edmund's 43 years), only a few years older than Edmund's own children, and was the middle child of a family of seven. According to Edmund's great-grandson Noël Crosse [E-mail 29 Dec 2022], she had been a schoolfriend of one of Edmund's daughters - in fact, given the ages of the various children, it seems most likely that Ada's younger sisters Edith and Jessie (born 1870 and 1871 respectively) had been friends of Edmund's daughters Lucy and Alice (born 1873 and 1874). Ada's father's occupation is given on his census returns as "stock exchange dealer", though the probate value of his estate in 1917 is only £666, suggesting that he wasn't an especially rich one. The census returns give various addresses in Surrey for the family, that for 1891 being at Long Ditton, which lies across the river from Hampton Court, just upstream from Teddington, again fitting with the description in the book. The crudeness of Marmaduke's language, and his evident contempt for his proposed bride, seem more likely to be an embellishment by the author, resulting from an antipathy he later developed towards Edmund after he failed to make good on the financial expectations Henry had of him — this is discussed further below.

Marriage, Separation, and the End of a Legal Career

In April 1891, at St Stephen's Church, Haverstock

Hill, Henry married Margaret

Rebecca Rance

(1868-1954), the daughter of an accountant living on South Hill Park,

Hampstead [CLA/60/1], about a mile from

Henry's lodgings on Steele's Road [CLA/59/1] —

perhaps they met walking on nearby Hampstead Heath. The marriage was

not a successful one,

and it ended in a scandalous divorce case in March 1896, when Margaret

alleged adultery and cruelty on Henry's part; he responded with an

allegation of adultery between her and her cousin, Dr Francis

Humphreys. The hearing took place before Sir Francis Jeune

(later Lord St

Helier), President of the Probate, Divorce and Admiralty Division of

the High Court, who sat with a special jury; there were QCs

representing

both sides, and the proceedings were widely reported in the both local

and national press [CLA/63], whose accounts have

provided most of the following

details, along with the sketches of the main protagonists.

Following their wedding, Henry and Margaret lived together at a house in Harlesden in north London, called The Maisionette. In 1893 Henry made the acquaintance of "a waitress at a London restaurant" named Rachel Elizabeth Ockelford, known as "Ray". She was a cockney girl, born at Mile End in 1868 [CLA/62/1]. There are some inconsistencies in the various GRO Registration entries and census returns, and in the spelling of her surname (and I can find no record for her in the 1881 census) but her parents appear to have been William and Rachel Tupper Ockelford. His family ran a successful upholstery business [CLA/62/5] and they were married in 1865 [CLA/62/6]. He is shown as a furniture salesman on Rachel's birth certificate but the family may have fallen on hard times, as he died in 1875 [CLA/62/7] and Ray's mother in 1888 [CLA/62/8], when Ray was 19. In the 1891 census [CLA/62/3] Ray is shown working as a servant at the Castle and Falcon Hotel on Aldersgate in the City of London, and it is quite likely that Henry met her through his work on tenancy agreements for a brewery, discussed below.

Meanwhile, Margaret began to feel that her husband was neglecting her, and some time later, while they were on a visit to Norfolk, she found him reading a letter addressed to "my darling boy" and signed "your loving Ray". On returning home she challenged him on this, but the explanation he offered was unsatisfactory, and she refused to sleep in the same room as him. Henry was incensed, and spent the night outside the door "moaning and groaning and asking me to forgive him", and at one point calling out "I have got a revolver and will make a clean sweep of the whole show". She also claimed that her servant had shown her a photographic negative found in the house with an image of a young girl "in scanty attire".

Dr Humphreys appeared as a witness on his cousin

Margaret's behalf, and

the counter-suit may well have been aimed at trying to discredit his

evidence.

During the early years of the marriage, when he was a medical student,

he had visited the Clabburns regularly, and had nursed Margaret at

Henry's request when she had been ill. He said in his evidence that he

had become concerned about Henry's drinking (sometimes as much as

bottle of whisky in an evening) which had caused a strain in the

marriage, and that Henry had admitted his adultery to him saying, "The

game is up, I am found out." He also claimed that he had seen Henry

threatening Margaret, and had taken a revolver from him three times; he

said that he had been concerned that murder or suicide would take place

when Henry was drunk.

In

an illustration of the problems encountered by late

Victorian women in obtaining divorces, even in the face of blatantly

appalling behaviour by their husbands, the Judge suggested that in

order

to obviate going into a painful inquiry into the other part of the

case, Margaret should be satisfied with a decree of separation, and

should drop the allegation of cruelty, while Henry dropped his

allegation of adultery with Dr Humphreys, and admitted his adultery

with Ray Ockelford (which his counsel had effectively already

conceded). This was agreed to by the parties, the Jury formally found

that Henry had committed adultery, and a decree of judicial separation

was granted, with costs (though Dr Humphreys' costs were not allowed).

The separation order allowed Margaret to escape from the marriage, but there appears to have been no order for payment of alimony or other maintenance, and of course neither party was free to remarry. Margaret is shown in subsequent censuses living with her widowed father (1901), and later (1911, 1921) with her clergyman brother (who became Vicar of St Margaret's Leytonstone) and his family, and they presumably provided for her financially. In the national registration of 1939 she is shown as boarding in Hastings, widowed with private means. After the war she lived at Selsey in Sussex, and her Will (dated 9 Dec 1951) leaves "all of which I die possessed" to her nephew Derek George Holwell Rance, a schoolmaster at Brentwood School in Essex, "to be used for the education of his son Nicholas Anthony Rance." She died, aged 85, on 5 Feb 1954 at the Royal West Sussex Hospital in Chichester, with her estate valued at £1046 [CLA/60].

The publicity surrounding the case would not have done Henry's reputation any good, nor his prospects for advancement in his legal career, and it was almost certainly a major factor behind its termination. To the extent that the portrayal of Rupert Claybrooke in his novel Celibate Sarah is autobiographical, Henry glosses over the entire episode, though there is a brief passage (p. 49) which is perhaps a guarded reference to it, where he mentions "certain complications in [Rupert's] private life (which form a drama of surpassing interest in themselves, and which may see the light of publication after the death of one of the dramatis personae concerned)." Presumably the relevant dramatis persona was either Margaret or Rachel, both of whom outlived Henry, but it is possible that some fictionalised account of the affair found its way into one of the novels I have not yet had a chance to read. The divorce case probably also ended any prospect that he might look to his wealthy brother-in-law Edmund Meredith Crosse for further financial support, and this is likely to account for the portrayal of Crosse (as Marmaduke Redfern) in the novel as a "cad" (p. 22) who had reneged on his promises (p. 47).

The novel (pp. 45ff) also provides a description of the type of work that Henry may have done as a solicitor, though I have not been able to confirm any of this from independent sources. His alter ego Rupert is granted a managing clerkship with his firm of Chapman and Starling, and is put in charge of the affairs of a brewery, dealing with the various agreements needed for changes of tenancy in their tied houses, applications for licences, etc. This frequently requires him to spend long hours late into the evening in public houses — exactly the type of situation which might have brought him into contact with the likes of Ray Ockelford. Rupert becomes worn out by the mental strain of the work, and the meannesses of his private clients, and recognises that his expenditure in London exceeds his income; his doctor advises him that he should move to the country and live as simply and primitively as possible. He has always had a fancy for writing, and his friend Harry Lyndon, who has "made a name for himself in the world of letters" offers to help him with commissions for articles and reviews, and he therefore decides to move back to East Anglia and live for a while with his sister, later moving to a small cottage "on the edge of the marsh".

An East Anglian Thomas Hardy?

Whatever the causes of it, there is no doubt that Henry made a change of home and career in the late 1890s, exactly equivalent to Rupert's. To further emphasise his changed life, Henry also took a new name, becoming James Blyth, and all his subsequent literary efforts were published under this name. Blyth was his mother's maiden name, and this may also reflect a wish to associate himself with the memory of the mother he had lost at such a sensitive age. Ray Ockelford accompanied Henry in his flight to the countryside, and also adopted his new name: they are recorded as living together as Mr and Mrs Blyth in the 1901, 1911 and 1921 censuses [CLA/59], though there is no record of any marriage (which, as he was not divorced, would have been bigamous). In 1901 and 1911 James Blyth's occupation is given as "author". Rupert's literary friend Harry Lyndon appears to represent Max Pemberton, a contemporary of Henry's at Cambridge, and a well-known novelist, who was knighted in 1928. Pemberton edited Cassell's Magazine in the early 1900s when it published several articles by James Blyth [CLA/58/2], so he obviously made good on his promises.

Initially Henry

also seems to have been short of money (on p. 50 of Celibate Sarah it

is stated that Rupert has fifty pounds to his name), and he

sold some of the

Sandys pictures he had inherited from his father in 1898 [CLA/29

p. 244]; another source [CLA/3/6/1]

suggests that he had to sell his

photographic equipment. His first novel, Juicy Joe: A Romance of Norfolk

Marshlands,

was not published until 1903 [CLA/61/1], probably about 6 years

after

he had moved back to East Anglia. After that they followed fairly thick

and fast for the next twenty years, with a variety of publishers: 1907

alone saw five novels (all with different publishers) and a collection

of short stories, and the British Library catalogue lists no fewer than

58 titles, 18 of which

went to second editions. Most of these are novels with a few

collections

of

short stories, and one edited collection of letters between the poet Edward Fitzgerald (translator of

the Rubaiyat of Omar

Khayyam) and a Lowestoft herring fisherman called Joseph

Fletcher. Two

books were collaborations with the writer Barry

Pain, who had also been a contemporary of Henry's at

Cambridge.

Initially Henry

also seems to have been short of money (on p. 50 of Celibate Sarah it

is stated that Rupert has fifty pounds to his name), and he

sold some of the

Sandys pictures he had inherited from his father in 1898 [CLA/29

p. 244]; another source [CLA/3/6/1]

suggests that he had to sell his

photographic equipment. His first novel, Juicy Joe: A Romance of Norfolk

Marshlands,

was not published until 1903 [CLA/61/1], probably about 6 years

after

he had moved back to East Anglia. After that they followed fairly thick

and fast for the next twenty years, with a variety of publishers: 1907

alone saw five novels (all with different publishers) and a collection

of short stories, and the British Library catalogue lists no fewer than

58 titles, 18 of which

went to second editions. Most of these are novels with a few

collections

of

short stories, and one edited collection of letters between the poet Edward Fitzgerald (translator of

the Rubaiyat of Omar

Khayyam) and a Lowestoft herring fisherman called Joseph

Fletcher. Two

books were collaborations with the writer Barry

Pain, who had also been a contemporary of Henry's at

Cambridge.

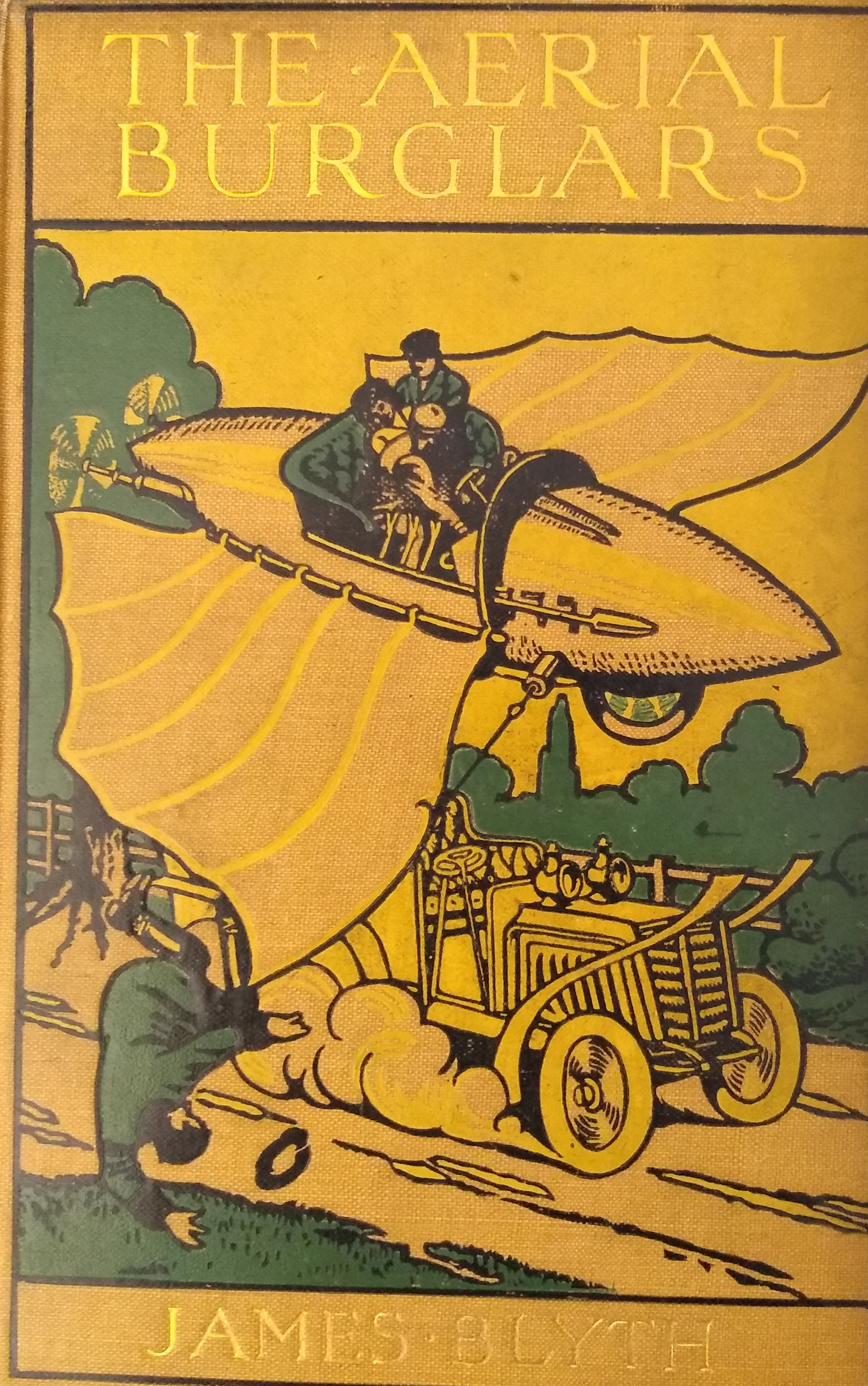

Blyth also branched out into historical adventure stories,

such as The

Kings Guerdon (1906) and Napoleon

Decrees (1914), and into futuristic (if not exactly

science fiction) novels involving flying machines (The Aerial

Burglars, 1906; The

Peril of Pines Place, 1912) and a

mind-altering machine operating through "Hertzian waves" (Ichabod, 1910). In

particular, he took to a genre known as

"invasion scare" fiction (The

Swoop of the Vulture, 1909; Ichabod,

1910), which became popular in the years leading up to the First World

War, and was also indulged in by his friend Max Pemberton in his Pro Patria

(1901). These stories were often politicised, warning of the threats

posed by Germany, and are revealing of Blyth's conservative (not to say

reactionary) views.

Blyth also branched out into historical adventure stories,

such as The

Kings Guerdon (1906) and Napoleon

Decrees (1914), and into futuristic (if not exactly

science fiction) novels involving flying machines (The Aerial

Burglars, 1906; The

Peril of Pines Place, 1912) and a

mind-altering machine operating through "Hertzian waves" (Ichabod, 1910). In

particular, he took to a genre known as

"invasion scare" fiction (The

Swoop of the Vulture, 1909; Ichabod,

1910), which became popular in the years leading up to the First World

War, and was also indulged in by his friend Max Pemberton in his Pro Patria

(1901). These stories were often politicised, warning of the threats

posed by Germany, and are revealing of Blyth's conservative (not to say

reactionary) views.

A number of people have taken an interest in Blyth's work in the past fifty years. Foremost among these was the Norfolk book collector Ron Fiske (1938-2018) [CLA/66], who amassed a large number of Blyth's books, and was the principal source for an article about Blyth in the Eastern Daily Press in 1975 [CLA/3/6/1]. Margaret Langley (who in the 1990s lived in the Norwich house where Blyth grew up) read a number of his books and was the first to note that some passages in Celibate Sarah (1904) appeared to have an autobiographical basis [CLA/3/6/4]. Of the books she was able to obtain and read, Langley felt that some (Juicy Joe, Brumlingham Hall) were "real literature", and others (The Kings Guerdon, Napoleon Decrees) "good exciting adventure stories", while some (Amazement, Thora's Conversion) were marred by "chip-on-shoulder moralizing" [CLA/3/6/2]. According to Langley [CLA/3/5/6], Fiske partially completed a book about James Blyth, in which he tried to present material from his novels as "deathbed reflections" from the author. Langley felt that this didn't work, and that a straightforward anthology of passages from the novels, with explanatory notes, would be better. So far as I am aware, the project was abandoned, and I do not know if any material survives. Fiske's book collection was broken up and sold at auction in 2016 [CLA/66/3].

The editor of the Encyclopedia

of Science Fiction, John Clute, has taken a greater

interest

in the futuristic novels, and notes that The Swoop of the Vulture

(1909), in which Germany (the vulture) mounts an invasion of England in

1918, was spoofed the same year by no less a figure than P.G. Woodhouse

in his comic novel The Swoop! or How Clarence Saved

England (1909) [CLA/56/2].

A more in-depth analysis of Blyth's Ichabod (1910) is

offered by Harry Wood in his Island

Mentalities blog [CLA/56/3].

Wood notes that the novel is suffused by an antisemitism of

extraordinary vitriol,

though is unable to fully account for its

vituperativeness. Clute

also suggests that it is "robust even for the England of 1910", and

throwaway antisemitic comments appear in some of the other

novels. Wood

observes that Blyth's venom is also directed at the Germans ("jeering

Prussian sausage munchers") and that he actually mixes up his

derogatory epithets for Germans, Poles, Russians and Jews, irrespective

of their ethnic or religious background. Blyth's scorn is further

targeted at the "sickly sentimentality of Liberal governance", which

accords with Margaret Langley's comments about Blyth's "tub-thumping

anti-women's-lib stuff" in Thora's

Conversion [CLA/3/6/5].

In another blog post [CLA/56/4] Wood

comments that Blyth's

understanding of science was limited, though his dismissal of powered

flight in Ichabod

(1910) had been revised somewhat by the time of The Peril of Pines Place

(1912) — this comment seems to ignore the flying motor car which

appears in The Aerial

Burglars (1906) [CLA/56/2].

The editor of the Encyclopedia

of Science Fiction, John Clute, has taken a greater

interest

in the futuristic novels, and notes that The Swoop of the Vulture

(1909), in which Germany (the vulture) mounts an invasion of England in

1918, was spoofed the same year by no less a figure than P.G. Woodhouse

in his comic novel The Swoop! or How Clarence Saved

England (1909) [CLA/56/2].

A more in-depth analysis of Blyth's Ichabod (1910) is

offered by Harry Wood in his Island

Mentalities blog [CLA/56/3].

Wood notes that the novel is suffused by an antisemitism of

extraordinary vitriol,

though is unable to fully account for its

vituperativeness. Clute

also suggests that it is "robust even for the England of 1910", and

throwaway antisemitic comments appear in some of the other

novels. Wood

observes that Blyth's venom is also directed at the Germans ("jeering

Prussian sausage munchers") and that he actually mixes up his

derogatory epithets for Germans, Poles, Russians and Jews, irrespective

of their ethnic or religious background. Blyth's scorn is further

targeted at the "sickly sentimentality of Liberal governance", which

accords with Margaret Langley's comments about Blyth's "tub-thumping

anti-women's-lib stuff" in Thora's

Conversion [CLA/3/6/5].

In another blog post [CLA/56/4] Wood

comments that Blyth's

understanding of science was limited, though his dismissal of powered

flight in Ichabod

(1910) had been revised somewhat by the time of The Peril of Pines Place

(1912) — this comment seems to ignore the flying motor car which

appears in The Aerial

Burglars (1906) [CLA/56/2].

Whatever his aspirations, Blyth was certainly no Hardy, and his novels seem to be rather a mixed bag. Some of them are ingrained with the his own, sometimes obnoxious, personal prejudices, whether against individuals (especially where his characters represent real people) or against classes, nationalities or races, which can make for a "highly unpleasant reading experience" (Wood, CLA/56/3) for the modern reader. The principal enduring interest is probably his faithful reproduction of the Norfolk dialect, and occasional descriptive passages of the landscape of the marshes [CLA/56/5]:

As soon as the young moon had made an early retirement suitable to its tender age, and the marshes were left to their purple darkness under the stars which multiplied themselves a millionfold in the gloss of the dykes and winked at their cleverness in doing so, old Granny went clicketing down the loke across the big marsh to where the great black mill stands, which drains the whole of the Frogsthorpe level through the conduit of the mill dyke. The waters were low, and the mill stood swart and still in the hard clear starlight.

There is a willow that stretches athwart the widest part of the pool, where the fat roach lie waiting for the larvae of countless insects that still fall from the tremulous white glow of the leaves to the black depths beneath. Hither hobbled old Granny, and here through the night she sat out on the leaning trunk, over the water, till her incantations were complete, her mysteries of divination ended. The whisper of the wind before the dawn was stirring the willow leaves, and the pure fresh scent, the harbinger of sunrise, was upon the marshes ere her work was done. [Celibate Sarah, pp. 254-5]

Celibate Sarah — Merging Fact with Libellous Fiction

Celibate Sarah was Blyth's second novel, published in 1904, and the autobiographical nature of the background to the life of the main character, Rupert Claybrooke, has already been discussed, as has the basis of the minor character Marmaduke Redfern in Henry Clabburn's brother-in-law Edmund Meredith Crosse. Much of the main plot of the novel is concerned with Rupert's sister Laura, clearly modelled on Henry Clabburn's younger sister Lucy Clabburn (1856-1914) and her companion, the eponymous "celibate" Sarah Chindaffy, who is portrayed as the villain of the piece. In another nod to Thomas Hardy, her surname of Chindaffy is said (p. 3) to be a corruption of the Norman name "Chien-de-feu", representing a degenerated aristocratic family that had fallen on hard times, like Tess Derbyfield's descent from the ancient d'Urbevilles.

Sarah is equally clearly based on Clara Eliza Shardelow (1849-1932), who is recorded as resident in the Clabburn household with Lucy and her father in the 1881 census, and as living as a "companion" with Lucy in the three remaining censuses of Lucy's lifetime. The link between Clara and the novel is also made on a Shardelow genealogy website [CLA/65/7]. Neither woman ever married, and Clara was the principal beneficiary of Lucy's Will, so in these more modern days of equal marriage it seems reasonable to regard them as a couple, on which basis I have included Clara on my Clabburn family tree as Lucy's unmarried life-partner. This is essentially the way the relationship is portrayed in the novel, though there Sarah is shown as scheming and manipulative, with the objective of securing Laura's inheritance for herself and her nephew Bertie. The novel has no explicit indication that the relationship between the two women is a sexual one, though it does make it clear that they share a bed (p. 217), but that would probably not have been unusual in the late 19th century.

| Character in novel | Real-life model |

| Rupert Claybrooke | Henry James Catling Clabburn (James Blyth) |

| William Leicester Claybrooke | William Houghton Clabburn |

| Laura Claybrooke | Lucy Clabburn |

| Sarah Chindaffy | Clara Eliza Shardelow |

| Peggie Noddyfield (née Chindaffy) | Martha Blunderfield (née Shardelow) |

| Phillip Noddyfield ("Noddy") | Francis Browne Blunderfield |

| Bertie Noddyfield | Frank Arthur Blunderfield |

| Marmaduke Redfern | Edmund Meredith Crosse |

| Lily Costa | Ada Caroline Price |

| Harry Lyndon | Max Pemberton |

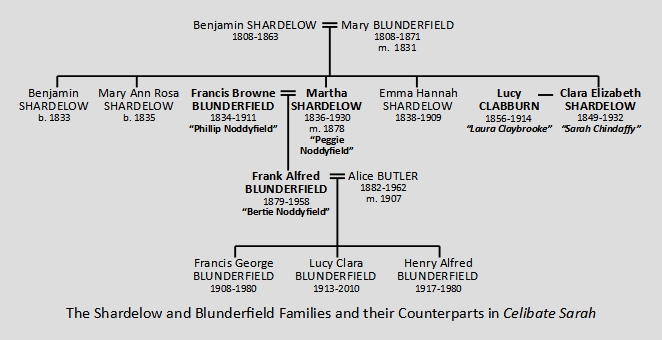

When Clara Shardelow's own real-life family is examined in more detail, the parallels with the characters depicted in the novel become even more obvious and blatant. Her parents were Benjamin and Mary Shardelow (see family tree below) and her father is recorded as a plumber and glazier in the 1851 census; Clara was actually baptised on the same day as Lucy's elder brothers William and Arthur [CLA/65/1] so the families would clearly have known each other, and it is likely that Benjamin did maintenance work in the Clabburn household. In the novel, Sarah has an elder sister (and co-conspirator) Peggie, who corresponds to Clara's elder sister Martha Shardelow (1836-1930). Peggie's husband is the blind Phillip Noddyfield (p. 63), who represents Martha's real-life husband Francis Browne Blunderfield (1834-1911), recorded in the 1851 census at the blind school in Norwich [CLA/65/6]. You couldn't make it up, and James Blyth obviously didn't. Martha and Francis had a single son, Frank Alfred Blunderfield (1879-1958), who is recorded in the 1901 and 1911 censuses as a carpenter. He appears in the novel as Peggie's half-wit son Bertie, who makes coffins, and carries messages between his aunt and mother.

In

the story, following William Claybrooke's funeral, the provisions of

his will are outlined; they more or less precisely reflect those of

W.H. Clabburn's [CLA/10] with modest bequests to his sons, the bulk of

his estate left in trust for Laura, and Rupert and William's solicitor

as

Trustees. Laura and Sarah move to a house at St Mary's-on-the-Fen

(Beccles) on the River Saelig (the Waveney) inland from Herringhaven

(Lowestoft), where they keep chickens. The house is called "The

Limes"; in real life Lucy and Clara lived at Linden House, London Road,

Beccles, and of course linden and lime are alternative English names

for trees

of the genus Tilia.

Laura,

aged nearly 30 at the start of the novel, is described (p. 3) as having

suffered from infantile paralysis (poliomyelitis) in childhood, as a

result of which she had had little education, and remained of "weak

intellect" and dependent on her companion. It is suggested that

in the years immediately following the move, she takes to

over-indulgence in strong drink, and puts on weight (p. 54). When

Rupert leaves London, he comes initially to stay at The Limes, and

Sarah suggests that a cottage her sister Peggie has to let might suit

him. They go to see it, in the village of Frogsthorpe, about 7 miles

from St Mary's. From the description on p. 69 Frogsthorpe appears to

represent either (or both) Fritton or Thorpe-next-Haddiscoe on either

side of the River Waveney and the Haddiscoe Cut (which shortcuts a

large

meander in the river) — James and Ray Blyth are shown as

living at the

former in the 1901 census [CLA/59/2], while the Blunderfields

are at the latter.

Sarah and Peggie consult a local witch as to how to sever the new-found closeness between Rupert and Laura — Laura is considering leaving the bulk of her trust fund (the capital of which she cannot touch in her lifetime, but which she can bequeath in her will) to her now impoverished brother. The plot involves Sarah allowing Rupert's pedigree bulldog to attack Laura's beloved terrier, which dies as a result, and Rupert is banned from ever visiting The Limes again.

Meanwhile, Rupert has fallen in love with a village girl called Bertha Heron, who lives in the next door cottage with her father and brothers, and nurses her through an illness. Following her father's death, they are married. There is no obvious real-life model for Bertha, but she may of course be partly based on Blyth's common-law wife, Ray Ockelford. His financial situation has further deteriorated, and though he has completed a novel, no publisher appears interested. He decides to go to sea with a fishing boat to earn money to send to his wife. "Old Granny", the witch, has moved into Bertha's family's old cottage, and when she falls ill, Bertha nurses her. Thus when the news comes that Rupert's boat has been lost at sea, Old Granny, touched by Bertha's kindness, uses her clairvoyant powers to reassure her that Rupert is still alive. At the same time, a letter is received from a publisher accepting Rupert's novel, and offering an advance of £25.

Though Laura has now made a will in Sarah's favour, the news of Rupert's apparent death leaves her overcome by guilt, and she turns on Sarah, who goes to plot further with Peggie. In her absence, Laura becomes despondent and resorts to the whisky bottle, making her more pliant when Sarah returns. But Sarah makes a mistake in revealing that Bertha is expecting Rupert's baby, and Laura decides to give Sarah only a life interest in her money, with the capital destined for Rupert's unborn child. Old Granny has now turned her magic powers to Bertha and Rupert's side, but she pretends still to help Sarah and Peggie in their plotting, while telling them to hold back on the drugs and poisons she had given them to administer to Laura. Laura has become wise to Sarah's evil intentions, but is kept prisoner in her room. In the nick of time, Rupert reappears (he had been rescued by a ship bound for the Americas, and taken many weeks to return) and arrives at the The Limes with his wife and a constable. Sarah jumps out of a window in an attempt to escape and is killed. Before she dies she asks to see her nephew Bertie, realising that "he oan't git the brass arter all", but asks him to "kiss yar ole aunt".

An epilogue describes Rupert's happy marriage and successful writing career, though he continues to live in the same area and makes little alteration to the simplicity of his life. Laura is said to look ten years younger, moves to live nearer her brother, and is devoted to her nieces and nephews, while Peggie and Bertie are driven mad by the failure of the plotting and are confined to the Eastern Counties Lunatic Asylum.

Clearly the main plot of the novel is pure imagination, however much the backgrounds of most of the characters are rooted in fact. It perhaps represents Henry Clabburn's fantasy of the course he would have wished the lives of his extended family to have taken, whilst indulging his own prejudices towards them. Trying to identify the elements of fact from the author's embellishments where there is no independent corroborating evidence is, however, difficult. Certainly, Clara Shardelow (Sarah) did not die jumping out of a window, but inherited Lucy Clabburn (Laura)'s trust fund when Lucy died in 1914, and lived off it for another 18 years; Henry Clabburn (Rupert) never had any children, and I have seen no evidence that he was ever shipwrecked; neither is there any indication that Clara's sister Martha (Peggie) nor Martha's son Frank Blunderfield (Bertie) were ever incarcerated in a lunatic asylum. Henry certainly did live quite close to Martha and her husband, and it is quite possible that he rented his cottage "On the Edge of the Marsh" from them. He certainly struggled financially until his first novel was published, and might well have taken other employment to make ends meet. Ron Fiske suggested that he might have done some teaching [CLA/3/6/1], but it is also possible that he crewed on a fishing boat — his 1908 book Edward Fitzgerald and Posh: Herring Merchants [CLA/61/17] shows he had some connections with the trade. It is also possible that Lucy had alcoholic tendencies: her death at the age of 57 was due to "acute congestion of the liver" [CLA/68].

The novel makes reference to some family portraits, and in particular Marmaduke Redfern indicates (p. 31) that he would like to buy"your mother's portrait by Watts ... I'll go to a couple of hundred for it". This is likely to be a reference to the magnificent 1860 oil portrait of Hannah Clabburn by Frederick Sandys which is now at Norwich Castle Museum [CLA/29 2.A.4]. Rupert indicates that "we shan't sell the portraits, thank you", upon which Marmaduke ups his offer to two fifty. In actual fact the Sandys portrait and the later chalk drawing [CLA/29 2.A.124] were retained by Lucy Clabburn who sold them in 1908. Henry Clabburn retained some of the other family portraits, including those of his father [CLA/29 3.6 and 3.7] but sold them, as mentioned above, in 1898. Edmund Meredith Crosse had the portraits featuring his first wife - these were, however, probably in her possession before her death, and would thus naturally have passed to her husband. The portrait of Henry's and Lucy's grandmother, Elizabeth Clabburn [CLA/29 2.A.29], also found its way to Edmund, and he may possibly have purchased it in the probate sale of W.H. Clabburn's effects.

I have suggested above that the very uncomplimentary portrayal of Marmaduke Redfern in the novel is more a reflection of Henry Clabburn's disappointment that his real-life counterpart Edmund Meredith Crosse had failed to provide him with the financial support he thought he had been promised, rather than any real indication of Edmund's character. Certainly Crosse and Blackwell were known as benevolent employers and philanthropists [CLA/64, p.37] and set up a savings bank (with preferential interest rates) and sports and recreation clubs for their employees [CLA/67]. An anecdotal story passed from my own grandmother, Ethel James (née Clabburn) via my mother claimed that "Mr Crosse" helped her family financially after the death of her father Arthur Clabburn (Henry's brother) in 1901. In the novel Marmaduke appears to have little more than contempt for his second bride, but in fact Edmund's second marriage produced six children between 1891 and 1903 (to add to the five surviving ones from his first marriage). Family relationships were certainly not perfect and, according to Noël Crosse, his grandfather Edmund Mitchell Crosse (1882-1963) (one of Edmund Meredith Crosse's sons by his first marriage) loathed his stepmother, but wept all night when his father died in 1918.

However much they may have been blackened in the novel, the similarities between the characters portrayed and their real life counterparts are so blatant, and so thinly disguised, that it is difficult to see how any sort of relationship between Henry Clabburn and his sister Lucy, her partner Clara Shardelow, and Clara's extended family, could have survived publication of the novel in 1904. The derivation of some of the fictional names from the real ones (Claybrooke for Clabburn, Noddyfield for Blunderfield) would alone have made the connection obvious not just to the individuals concerned, but to anyone with a passing knowledge of the families. As discussed above, Henry appears to have regarded his three elder brothers as "failures", and I have seen no indication that he ever had any contact with the only one of them remaining in England (Arthur — my great-grandfather, a struggling artist), nor with his widow and children after his death in 1901. He had also fallen out with his brother-in-law Edmund Meredith Crosse (Marmaduke Redfern), and so it's not that surprising that he fell out with his surviving sister as well. Possibly he resented the fact that she had inherited (at least a life interest in) the bulk of their father's estate, and perhaps she, like Edmund Crosse, was unwilling to offer him as much financial support as he would have liked. He might also have disapproved of Lucy's (possibly lesbian) relationship with Clara Shardelow, or simply the way in which Clara had inveigled her way into the family after their mother's death. His particular dislike and contempt does seem to centre on Sarah, Clara's counterpart in the novel, and her family. A complication in the family estrangement would have been Henry's role as trustee to Lucy's inheritance, which would have involved managing the investments and paying the income to her. An opportunity for further research might be to see if there is any evidence that Lucy tried to have him removed as a trustee.Ron Fiske is quoted [CLA/3/6/1] as suggesting that Blyth's "novels that followed Juicy Joe were based, perhaps too closely, on fact. Some of them were not far short of libellous of local dignitaries, and it is possible that Blyth was hounded out of the county by the threat of a lawsuit". Clara Shardelow and the Blunderfields (not to mention Edmund Crosse) could certainly have found some basis in Celibate Sarah for such a suit. Fiske's evidence is not given, and further research may rediscover it, or the real-life basis of material in any of Blyth's later novels (which I have not yet read). Certainly by the 1911 census [CLA/60/3], James and Ray Blyth are shown as living in Pakefield, a suburb of Lowestoft, rather than Fritton, where they were in 1901 — technically across the border in Suffolk, but not far away.

There

is an interesting postscript to the real-life counterpart of one of the

characters in the novel, which brings the story right through to the

21st century. Frank Blunderfield, the model for Sarah's nephew Bertie

(though there is no evidence that he was a half-wit) married Alice Butler

(1882-1962) in 1907 and they went on to have three children, Francis George Blunderfield

(1908-1980), Lucy Clara Blunderfield

(1913-2010), and Henry

Alfred Blunderfield (1917-1980). Frank is recorded on Lucy Clabburn's death certificate in 1914 [CLA/68] as having been present at her death and his address is given as Linden House, the house she shared with his aunt Clara Shardelow

(presumably, therefore, he and his family were living there too). His daughter Lucy Clara

is quite clearly named for the two ladies, suggesting that he was very

close to and fond of them. When Clara died in 1932 she left her entire

estate of just under

£2000 net (equivalent to about £165,000 in 2023, and

ultimately derived from the remains of W.H. Clabburn's fortune) in

trust

for Frank and his descendants — so actually, he did "git the

brass

arter all". What a pity I didn't do this research twenty years ago,

when the nonagenarian Lucy Clara Blunderfield might have been able to

shed light on the two women whose names she carried for nearly a

century.

There

is an interesting postscript to the real-life counterpart of one of the

characters in the novel, which brings the story right through to the

21st century. Frank Blunderfield, the model for Sarah's nephew Bertie

(though there is no evidence that he was a half-wit) married Alice Butler

(1882-1962) in 1907 and they went on to have three children, Francis George Blunderfield

(1908-1980), Lucy Clara Blunderfield

(1913-2010), and Henry

Alfred Blunderfield (1917-1980). Frank is recorded on Lucy Clabburn's death certificate in 1914 [CLA/68] as having been present at her death and his address is given as Linden House, the house she shared with his aunt Clara Shardelow

(presumably, therefore, he and his family were living there too). His daughter Lucy Clara

is quite clearly named for the two ladies, suggesting that he was very

close to and fond of them. When Clara died in 1932 she left her entire

estate of just under

£2000 net (equivalent to about £165,000 in 2023, and

ultimately derived from the remains of W.H. Clabburn's fortune) in

trust

for Frank and his descendants — so actually, he did "git the

brass

arter all". What a pity I didn't do this research twenty years ago,

when the nonagenarian Lucy Clara Blunderfield might have been able to

shed light on the two women whose names she carried for nearly a

century.

Return to London, Teaching, and Death

The

last of Blyth's books was published in 1922, when he was 58, but at

least a year before that he and Ray had moved back to London, and

are recorded in Fulham in the 1921 census [CLA/59/4].

His occupation is given as Assistant Director of Studies at the London

School of Journalism, which had been founded in 1920 by

Blyth's University friend and fellow-novelist, Max Pemberton, with funding from

the press baron Lord

Northcliffe. A 1922 advertisement for the college [CLA/58/1]

lists

Blyth among the tutors, who also included such luminaries as Sir Arthur

Quiller Couch. Just as Pemberton helped Blyth when he began his writing

career, the job at the London School of Journalism may have given him

some of the

financial security that his freelance writing career did not.

Unfortunately no archives from the early years of the (still

flourishing) London School of Journalism have survived, which might

have shed further light on Blyth's career there.

The

last of Blyth's books was published in 1922, when he was 58, but at

least a year before that he and Ray had moved back to London, and

are recorded in Fulham in the 1921 census [CLA/59/4].

His occupation is given as Assistant Director of Studies at the London

School of Journalism, which had been founded in 1920 by

Blyth's University friend and fellow-novelist, Max Pemberton, with funding from

the press baron Lord

Northcliffe. A 1922 advertisement for the college [CLA/58/1]

lists

Blyth among the tutors, who also included such luminaries as Sir Arthur

Quiller Couch. Just as Pemberton helped Blyth when he began his writing

career, the job at the London School of Journalism may have given him

some of the

financial security that his freelance writing career did not.

Unfortunately no archives from the early years of the (still

flourishing) London School of Journalism have survived, which might

have shed further light on Blyth's career there.

Blyth and Ray are recorded at 81 Clifton Road, Maida Vale, on electoral rolls for 1930 and 1931, and his death (aged 69) on 3 March 1933 is registered under both his names. An obituary appeared in the Cambridge Review of 19 May 1933, but I have not yet managed to obtain a copy. There is no probate record for him, and so he presumably had no significant assets to leave. Ray lived on until 1940 (when she was 71), and is shown in the National Registration of 1939 lodging in Southend-on-Sea, and doing casual nursing work [CLA/62/4].

Uncovering the details of Henry Clabburn / James Blyth's life has been a particularly fascinating piece of research, and has revealed some deeply disfunctional family relationships, as he evidently became estranged from all his siblings and their partners, as well as from his own first wife. The evidence presented in his divorce case does not show him in a favourable light, but whatever the origins of his affair with Ray Ockelford, they remained together for nearly 40 years. Being so much younger than his siblings, and packed off to boarding school on the death of his mother, cannot have helped him to form strong relationships with his elder brothers, but the collapse of his relationship with Lucy, worked out so vindictively in Celibate Sarah, seems particularly sad. There is no evidence that he attempted any sort of reconciliation with his brother Arthur's family - Arthur's grandson, Bob James, noted that Blyth was still living in London when he was at school at Westminster in the early 1930s, "and I never met him! What a shame!" [CLA/2/1] Given some of the attitudes and prejudices revealed in Blyth's writings, and my Uncle Bob's own more progressive views, I suspect that they would not have got on.

There remains much scope for further research into his life and writings; I would welcome contact from anyone else interested in him, or with information about him.

Copyright © 2023, John Barnard